Does higher educational attainment reduce an individual’s chance of being unemployed?

Note: If you would rather read this report in its original LaTeX form, click HERE.

Introduction#

In 2000, 44.8 million American adults aged 25 and older had a collegiate degree. By 2018, this number had increased to 77.1 million American adults (U.S Census Bureau, 2019). People are oftentimes incentivized to go to college by the stable job opportunities which arise through the acquisition of a college degree. In fact, a 2015 survey found that 91 percent of respondents listed improved employment opportunities as an important reason to go to college (New America, 2015).

With the demand for education growing rapidly, it’s important to recognize the potential benefits that higher levels of education might garner, one of which might be a reduction in the risk of being unemployed. This analysis asks the following question: does higher educational attainment reduce an individual’s chance of being unemployed?

The answer to this question could have interesting implications in the creation of public policy. Education provides positive externalities in the form of economic growth to communities. Positive externalities in this context are those which occur when the social benefit created by the consumption or production of education is higher than the private benefit to the individual receiving the education. This means that the good, education, is being underproduced. If unemployment rates decrease with higher attainment of education, it could be valuable for the government to incentivize individuals to acquire higher levels of education.

Current research indicates that having higher educational attainment may have some benefits for unemployed individuals. Data from the 1980 Census and Current Population Survey has found that high-school completion increases the chances of unemployed individuals getting hired for a new job by 40 percentage points. Furthermore, each year of schooling after high school completion increases the chances of getting hired for a new job by 4.7 percentage points (Riddell & Song, 2011). Aside from higher rates of re-employment, higher educational attainment generally leads to a lower chance of being unemployed (Vilorio, 2016).

Even though this question has been studied before, changing economies call for updated statistics on the subject. Job growth rates in different industries could change demand for individuals with different levels of educational attainment. For example, in recent years in the EU, the unemployment rate in fields such as social sciences and tourism has increased while more quantitative fields have remained stable in their unemployment rates (Scarpetta et al., 2012)

In some cases, certain sectors of the economy may be negatively impacted by different issues. For example, in 2020, several countries mandated COVID-19 lockdown orders which affected the economic well-being of restaurants, entertainment providers, etc. In the UK, young and lower-income workers were substantially more likely to work in sectors of the economy that were affected by the lockdown (Blundell et al., 2020).

I predicted that individuals with higher levels of education will have a lesser risk of unemployment, which is consistent with prior research on the topic done by (Vilorio, 2016) and (Riddell & Song, 2011). Theoretically, individuals that make up the labor supply are diverse in the skills they offer. While two individuals with vastly different levels of education attainment may both be part of the overall labor supply, the individual with more education is plausibly more qualified for a greater number of jobs. In this case, employers who look for specific skills in job candidates are more likely to hire the individual with a higher level of education, as that individual likely has more skills. Additionally, extra education also likely gives individuals an edge in job searching, which is desirable during periods of economic downturn.

The results of this analysis concur with my prediction. Unemployment likelihood decreased as educational attainment increased regardless of race. However, the analysis found that decreases in unemployment likelihood do not follow a linear pattern. Additional educational attainment faces diminishing marginal returns in unemployment risk reduction. The point at which the diminishing marginal returns begin partly depends on the race of an individual.

Data#

This analysis uses cross-sectional data from the 2019 American Community Survey, which is produced by the U.S Census Bureau. Individuals used in the sample are members of the labor force aged 16 to 65. These individuals reside in Washington DC or one of the other fifty states of the United States.

The dependent variable used will be employment status. Employment status has been split into two dummy variables: employed and unemployed.The independent variable of interest is educational attainment. Educational attainment has been split up into several finer categories (dummy variables) including Less than High School, High School or GED, Some College – DNF, Associate’s Degree, Bachelor’s Degree, and Graduate Degree. These variables were chosen because they all represent significant milestones in an individual’s educational attainment. Alongside these independent variables, this analysis will control for sex, race, age, number of children, and urban/rural status. These variables have also been made finer using dummy variables.

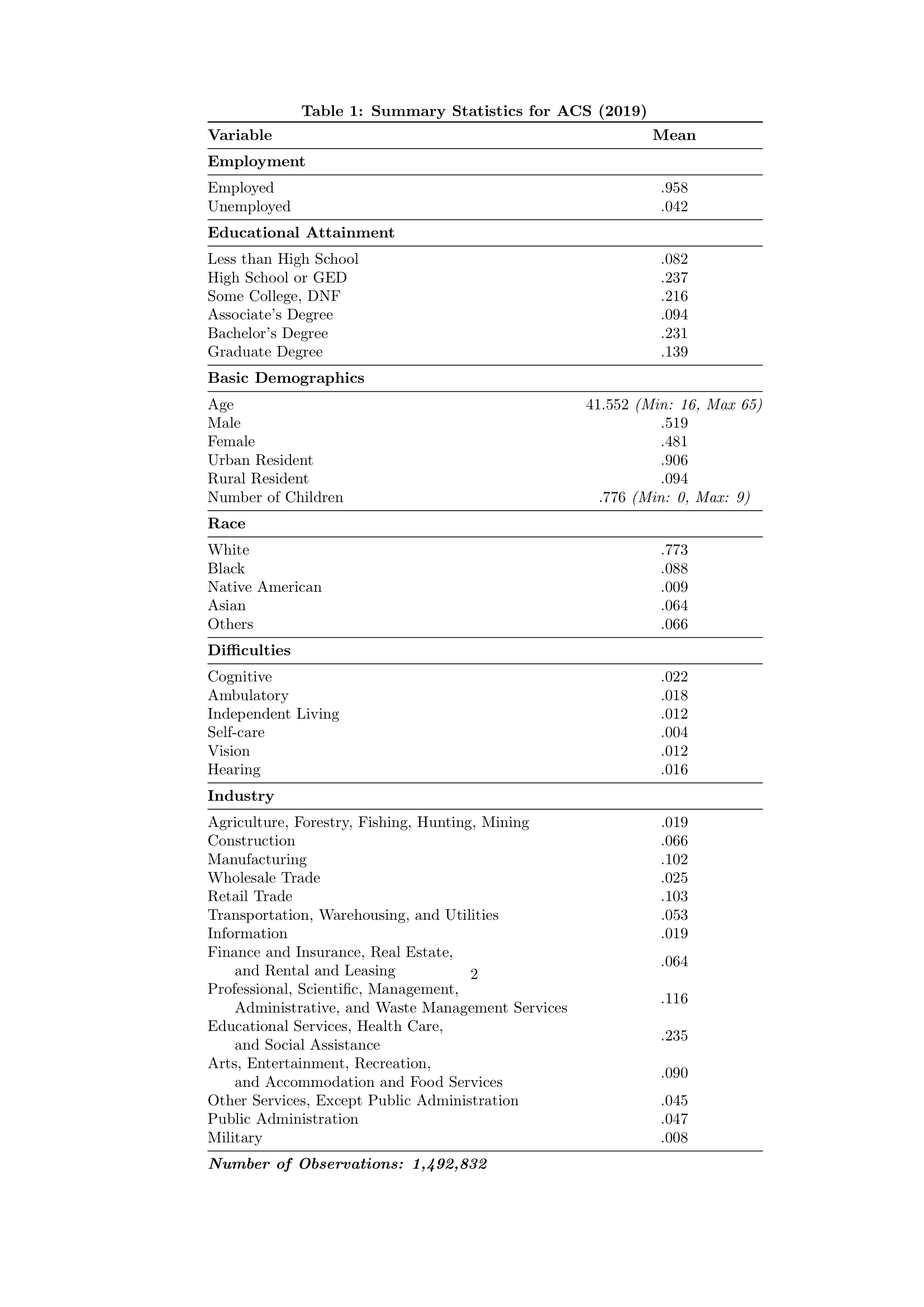

Table 1 is meant to provide insights about the sample being used in this analysis. As seen in the Table, 95.8 percent of individuals in the sample are employed. The remaining 4.2 percent of individuals are unemployed.

Members of the sample have diverse levels of educational attainment. Table 1 shows that 8.2 percent of individuals in the sample did not complete high school. Approximately 45.3 percent of individuals in the sample have a high school diploma or GED, and maybe an incomplete college education. The remaining 46.4 percent of individuals have a college degree, be it an associate’s, bachelor’s, or graduate degree.

Furthermore, 77.3 percent of the individuals in the sample are White and the average age of an individual in the sample is 44.152 years. The sample mostly represents individuals in urban areas, with only about 9.4 percent of individuals residing in rural areas.

Finally, individuals in the sample were employed in a range of different industries. The most concentrated industries, however, included Manufacturing (10.2%), Retail Trade (10.3%), Professional, Scientific, Management, Administrative and Waste Management Services (11.6%), and Educational Services, Health Care and Social Assistance (23.5%).

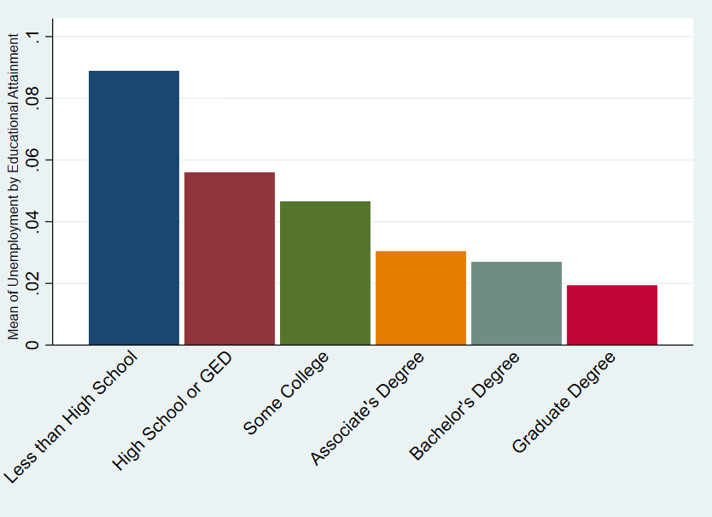

Figure 1 shows the means of unemployment by individual levels of educational attainment. According to the Figure, unemployment rates within each category decrease as the level of educational attainment increases. However, unemployment rates do not drop evenly between educational attainment categories. For example, the largest drop in unemployment rates occurred between individuals with less than high school education and individuals with a high school diploma or a GED. In the sample, the unemployment rate for individuals with a high school diploma or GED was 3.3 percentage points less than the rate for individuals with less than high school education. The second-largest drop in unemployment rates occurred between individuals with some college but no degree and individuals with associate’s degrees. The sample suggested that the unemployment rate for individuals with an associate’s degree was just .9 percentage points less than individuals with some college but no degree.

Results#

Empirical Regression#

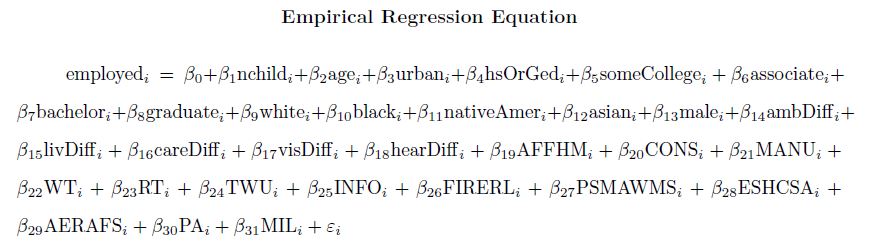

This analysis was performed using an Ordinary Least Squares Regression (OLS). The empirical regression measured the effect of different levels of educational attainment and other potentially significant variables on the chances of an individual in the sample being employed.

To prevent perfect multicollinearity, the following variables have been omitted from the regression: individuals residing in rural areas, individuals with less than high school education, individuals who are not White, Black, Native American, or Asian, individuals who are females, individuals with cognitive difficulties, and finally, individuals who work in the “other services, except public administration” industry. The regression coefficients will be interpreted in relation to the omitted variables.

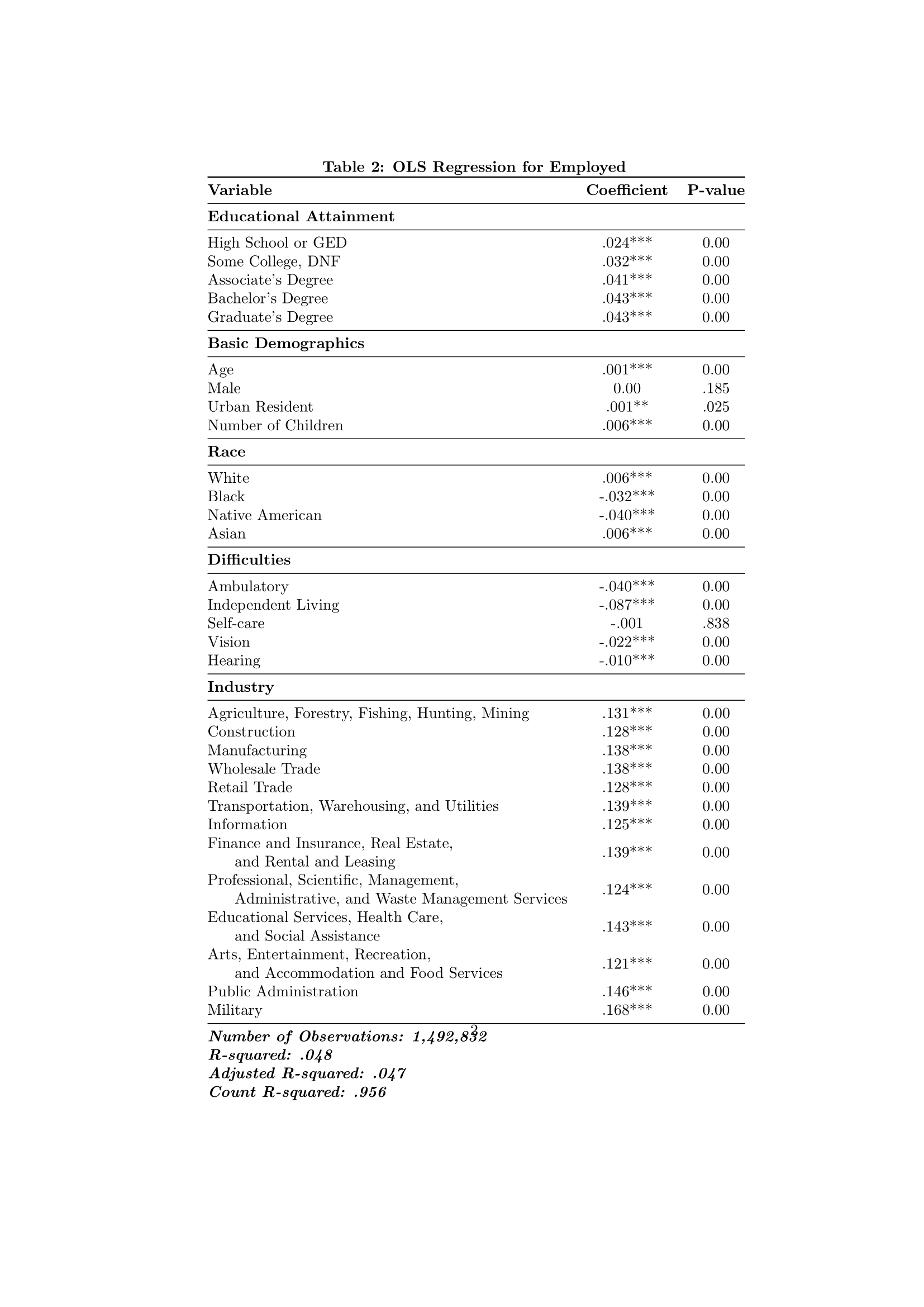

Table 2 suggests that the likelihood of an individual in the sample being employed increases with their level of educational attainment. Holding all else constant, an individual who has a high school diploma or GED is 2.4 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to an individual with less than high school education. With those same conditions applied, an individual with a graduate degree is 4.3 percentage points more likely to be employed. Levels of education between these two categories consistently show that the likelihood of being employed increases as an individual’s level of educational attainment increases.

The largest increase in employment likelihood happens between individuals with a high school diploma or GED and individuals with an associate’s degree. An individual who has associate’s degree is 4.1 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to an individual with less than high school education. Under the same conditions, an individual with a high school diploma or GED is 2.4 percentage points more likely to be employed. This means that the difference in employment likelihood between individuals with a high school diploma or GED versus individuals with an associate’s degree is 1.9 percentage points. Making the same comparison between individuals with an associate’s degree versus individuals with a graduate degree yields a less substantial difference of .2 percentage points.

Furthermore, all educational attainment, race, and industry categories were statistically significant at the 1% level. However, not all demographic categories were statistically significant. The regression model states that being a male is statistically insignificant at the 5% level, meaning that being male or female has a negligible impact on employment likelihood. Moreover, residing in an urban area was only statistically significant at the 5% level. Therefore, we can conclude that the area an individual in our sample resides in has an impact on their employment likelihood. However, this claim is made with less certainty that an impact exists compared to other categories such as educational attainment.

Regressions for White and Non-White Individuals#

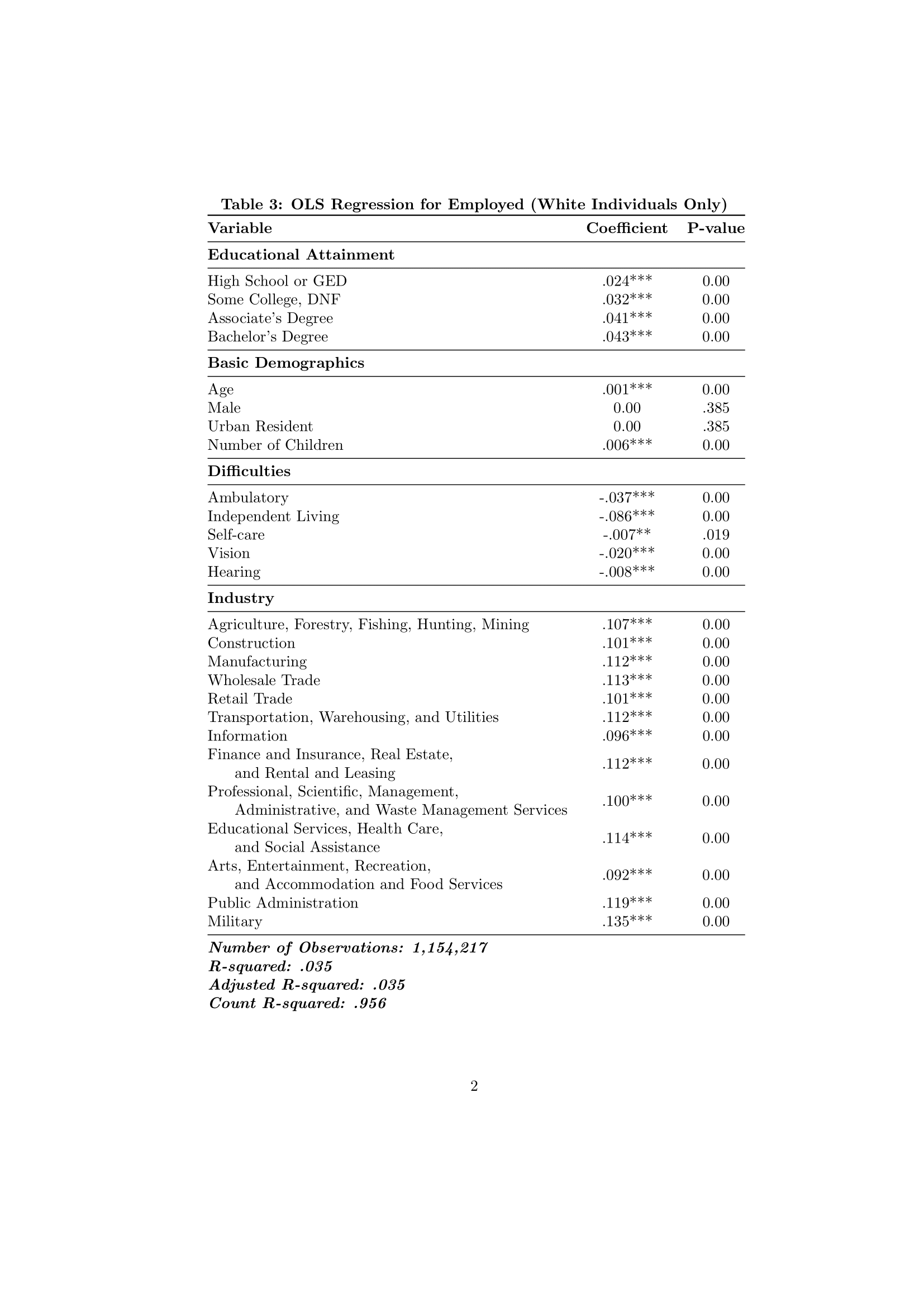

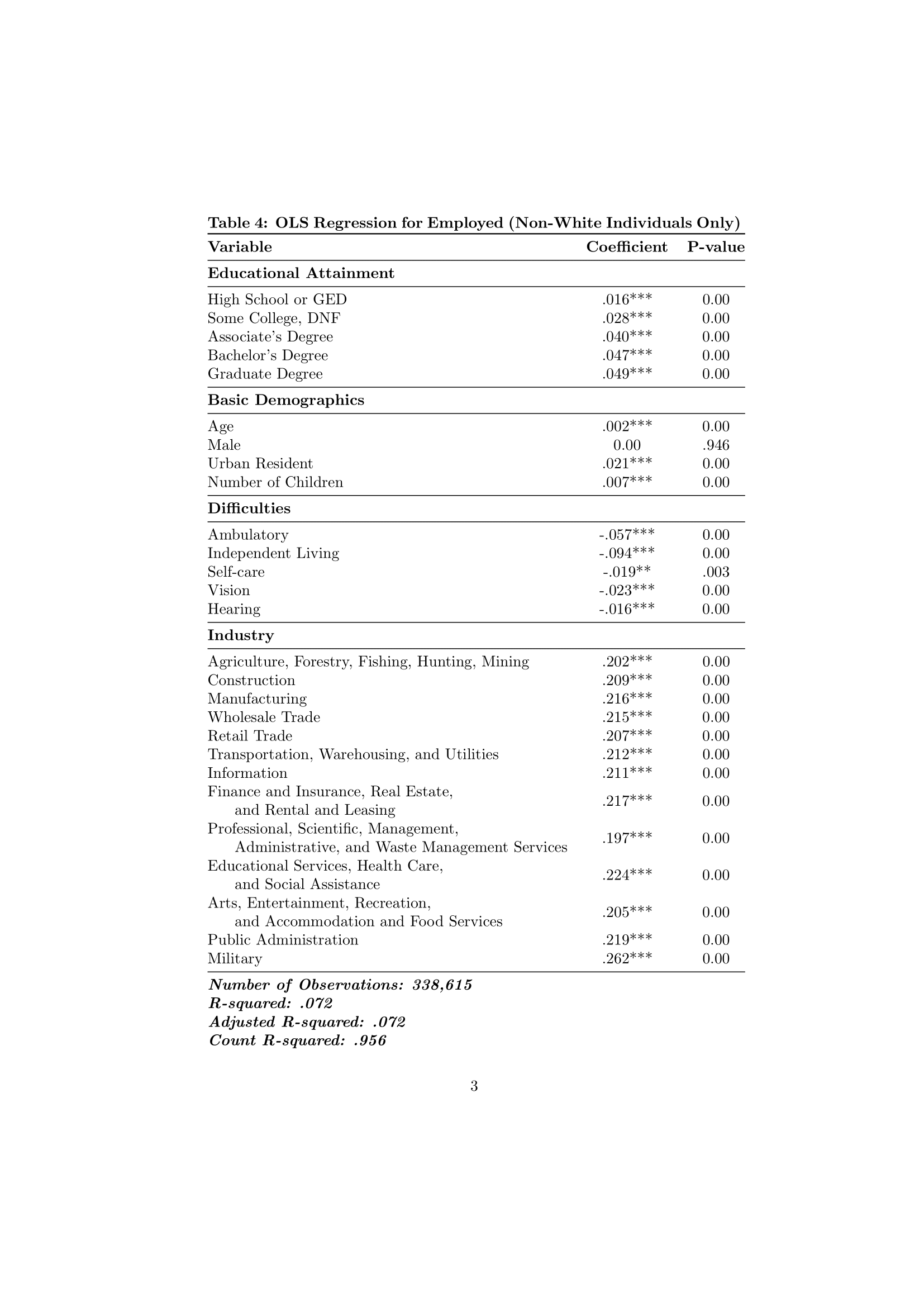

In the empirical regression, all races were statistically significant at the 1% level. However, 77.3 percent of individuals used in the regression were White. To further investigate the impact race has on employment likelihood, it’s valuable to consider regressions for White and non-White individuals separately. Both regressions are below.

For White individuals, the largest increase in employment likelihood happens between having a high school diploma or GED and having an associate’s degree. A White individual who has an associate’s degree is 4.0 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to a White individual with less than high school education, holding all else constant. Under the same conditions, a White individual with a high school diploma or GED is 2.4 percentage points more likely to be employed. This means that the difference in employment likelihood between White individuals with a high school diploma or GED versus individuals with an associate’s degree is 1.6 percentage points.

A similar trend is seen for Non-White individuals. A Non-White individual who has an associate’s degree is 4.0 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to a Non-White individual with less than high school education. This means that the difference in employment likelihood between Non-White individuals with a high school diploma or GED versus individuals with an associate’s degree is 2.4 percentage points.

The largest disparities between both regression models can be seen for individuals with some college. A Non-White individual with some college is 2.8 percentage points more likely to be employed compared to a Non-White individual with less than high school, holding all else constant. Furthermore, White individuals are 3.2 percentage points more likely to be employed under all the same conditions. As mentioned earlier, this trend was found for both White and Non-White individuals with a high school diploma or GED. These disparities suggest that White individuals without a college degree have an easier time finding employment than Non-White individuals without a college degree do.

A possible reason for the existence of these trends has to do with the geographical regions of residence for White and Non-White individuals. Non-White individuals are more likely than White individuals to live in communities with substantial poverty. Approximately 35 percent of Hispanic, 45 percent of Black, and 39 percent of Native American children lived in impoverished communities between 2006 and 2010, compared to only 12 percent of White children in the same time period (Austin, 2013). Available jobs in impoverished areas can be scarce because of the lower demand for goods and services from poorer individuals (Neumark & Meer, 2020). The lack of available jobs in these areas prevents individuals from finding employment.

As educational attainment increases, this trend reverses. Assuming the same conditions from past interpretations, increases in employment likelihood for Non-White individuals with a bachelor’s degree (.9 percentage points) are greater than the increases in employment likelihood for White individuals with a bachelor’s degree (.2 percentage points). This suggests that purely in terms of employment rates, earning a bachelor’s degree after an associate’s degree may be more valuable for Non-White individuals than it is for White individuals.

Labor is a mobile factor of production. Individuals in the labor force tend to go to areas where they can maximize their utility. Individuals with collegiate degrees may find more opportunities in areas without significant poverty and may choose to move to those areas. However, individuals with lower levels of education may not have comparable opportunities in other areas because of their comparatively low educational attainment. Therefore, because Non-White individuals are more likely to be living in impoverished neighborhoods than White individuals, higher education is more likely to enable them to move to areas with more opportunities where they can find employment. Thus, it is plausible that a bachelor’s degree may be more useful in decreasing their unemployment risk than it might be for a White individual.

Conclusion#

This analysis asked the question: does higher educational attainment reduce an individual’s chance of being unemployed? Based on the regressions performed, it can be concluded that higher educational attainment indeed decreases the likelihood of an individual being unemployed. However, the drop in unemployment probability was less significant between bachelor’s degrees and graduate degrees than it was between a high school diploma or GED and an associate’s degree. This suggests that higher educational attainment may provide diminishing marginal returns after a certain point in terms of unemployment risk. It should still be noted that while decreases in unemployment rates decrease, individuals with different levels of education compete for different types of jobs based on their qualifications.

Additionally, the regressions showed that factors other than educational attainment impact whether an individual is employed or not. A prominent example of this is the industry that an individual works in. Some industries have higher levels of unemployment than others do.

In all three regressions, all educational attainment and industry categories were statistically significant at the 1% level. Being male or female, however, had a negligible impact on our regression results. Living in an urban versus rural area also had a relatively small impact on our regression results.

To improve this analysis, I would control for marital status. If married individuals have a stable income from their spouse, they may have the opportunity to more carefully search for jobs that they are well-suited for, thus making them take more time in their job search. Furthermore, if a married individual had a stable income from their spouse, they may have less immediate pressure to find employment, and thus may apply to jobs at a slow rate.

Finally, it would be interesting to see this analysis done for periods of economic downturns such as 2008 or 2020. This analysis could also be useful in testing the theory that individuals with more skills or qualifications are more immune to unemployment when employment opportunities are scarce. This type of study could have interesting implications on public policy aimed at decreasing unemployment rates and/or stimulating economic activity.

References#

- America Counts Staff. (2019, May 23). Number of people with Master’s and doctoral degrees doubles since 2000. The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/ stories/2019/02/ number-of-people-with-masters-and-phd-degrees-double-since-2000.html.

- Blundell, R., Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., & Xu, X. (2020). COVID‐19 and Inequalities. Fiscal Studies, 41*(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12232

- College decisions Survey: Deciding to go to college. New America.

(2015, May 28).

https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/collegedecisions/. - U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

- Riddell, C. W., & Song, X. (2011). The impact of education on unemployment incidence and Re-employment Success: Evidence from the U.S. labour market. Labour Economics, 18(4), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2011.01.003

- Scarpetta, S., Sonnet, A., Livanos, I., Núñez, I., Craig Riddell, W., Song, X., & Maselli, I. (2012). Challenges facing European Labour markets: Is a skill upgrade the APPROPRIATE INSTRUMENT? Intereconomics, 47(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-012-0402-2

- Vilorio, D. (2016, March). Education matters : Career outlook. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/data-on-display/education-matters.htm.

- Austin, A. (2013, July 22). African Americans are still concentrated in neighborhoods with high poverty and still lack full access to decent housing. https://www.epi.org/publication/african-americans-concentrated-neighborhoods/.

- Neumark, D. (2019, January 22). Concentrated poverty and the disconnect between jobs and workers. https://econofact.org/concentrated-poverty-and-the-disconnect-between-jobs-and-workers.